In this post we will talk about HTTPS and how to add it to your GitLab Pages site with Let’s Encrypt. And you can find the original post at Tutorial: Securing your GitLab Pages with TLS and Let’s Encrypt. Here, I add my own exprience when following its guidance.

Why TLS/SSL?

When discussing HTTPS, it’s common to hear people saying that a static website doesn’t need HTTPS, since it doesn’t receive any POST requests, or isn’t handling credit card transactions or any other secure request. But that’s not the whole story.

TLS (formerly SSL) is a security protocol that can be added to HTTP to increase the security of your website by:

- properly authenticating yourself: the client can trust that you are really you. The TLS handshake that is made at the beginning of the connection ensures the client that no one is trying to impersonate you;

- data integrity: this ensures that no one has tampered with the data in a request/response cycle;

- encryption: this is the main selling point of TLS, but the other two are just as important. This protects the privacy of the communication between client and server.

The TLS layer can be added to other protocols too, such as FTP (making it FTPS) or WebSockets (making ws:// wss://).

HTTPS Everywhere

Nowadays, there is a strong push for using TLS on every website. The ultimate goal is to make the web safer, by adding those three components cited above to every website.

The first big player was the HTTPS Everywhere browser extension. Google has also been using HTTPS compliance to better rank websites since 2014.

TLS certificates

In order to add TLS to HTTP, one would need to get a certificate, and until 2015, one would need to either pay for it or figure out how to do it with one of the available Certificate Authorities.

Enter Let’s Encrypt, a free, automated, and open Certificate Authority. Since December 2015 anyone can get a free certificate from this new Certificate Authority from the comfort of their terminal.

Implementation

So, let’s suppose we’re going to create a static blog with Jekyll 3. If you are not creating a blog or are not using Jekyll just follow along, it should be straightforward enough to translate the steps for different purposes.

A simple example blog can be created with:

$ jekyll new cool-blog

New jekyll site installed in ~/cool-blog.

$ cd cool-blog/

Now you have to create a GitLab project. Here we are going to create a “user page”, which means that it is a project created within a user account (not a group account), and that the name of the project looks like YOURUSERNAME.gitlab.io. Refer to the “Getting started” section of the GitLab Pages manual for more information on that.

If you are using GitHub Pages, its not possible for you to get a SSL for your custom domain at present. So, GitLab might be a good choice if you need the https.

From now on, remember to replace YOURDOMAIN.com with your custom domain and YOURUSERNAME with, well, your username. ;)

Create a project named YOURUSERNAME.gitlab.io so that GitLab will identify the project correctly. After that, upload your code to GitLab:

$ git remote add origin git@gitlab.com:YOURUSERNAME/YOURUSERNAME.gitlab.io.git

$ git push -u origin master

OK, so far we have a project uploaded to GitLab, but we haven’t configured GitLab Pages yet. To configure it, just create a .gitlab-ci.yml file in the root directory of your repository with the following contents:

pages:

stage: deploy

image: ruby:2.3

script:

- gem install jekyll

- jekyll build -d public/

artifacts:

paths:

- public

only:

- master

This file instructs GitLab Runner to deploy by installing Jekyll and building your website under the public/ folder (jekyll build -d public/). You can find a previous post about the GitLab CI for your Jekyll site.

While you Wait for the build process to complete, you can track the progress in the Builds page of your project. Once it starts, it probably won’t take longer than a few minutes. Once the build is finished, your website will be available at https://YOURUSERNAME.gitlab.io. Note that GitLab already provides TLS certificates to all subdomains of gitlab.io (but it has some limitations, so please refer to the documentation for more). So if you don’t want to add a custom domain, you’re done.

Configuring the TLS certificate of your custom domain

Once you buy a domain name and point that domain to your GitLab Pages website, you need to configure 2 things:

- add the domain to GitLab Pages configuration (see documentation);

- add your custom certificate to your website.

Once you add your domain, your website will be available under both http://YOURDOMAIN.com and https://YOURUSERNAME.gitlab.io.

But if you try to access your custom domain with HTTPS (https://YOURDOMAIN.com in this case), your browser will show that horrible page, saying that things are going wrong and someone is trying to steal your information. Why is that?

Since GitLab offers TLS certificates to all gitlab.io pages and your custom domain is just a CNAME over that same domain, GitLab serves the gitlab.io certificate, and your browser receives mixed messages: on one side, the browser is trying to access YOURDOMAIN.com, but on the other side it is getting a TLS certificate for *.gitlab.io, signaling that something is wrong. That’s the same case for GitHub Pages, you can visit your site with https for *.github.io but not for your custom domain.

In order to fix it, you need to obtain a certificate for YOURDOMAIN.com and add it to GitLab Pages. For that we are going to use Let’s Encrypt.

Let’s Encrypt is a new certificate authority that offers both free and automated certificates. That’s perfect for us: we don’t have to pay for having HTTPS and you can do everything within the comfort of your terminal.

We begin with downloading the letsencrypt-auto utility. Open a new terminal window and type:

$ git clone https://github.com/letsencrypt/letsencrypt

$ cd letsencrypt

letsencrypt-auto offers a lot of functionality. For example, if you have a web server running Apache, you could add letsencrypt-auto --apache inside your webserver and have everything done for you. letsencrypt targets primarily Unix-like webservers, so the letsencrypt-auto tool won’t work for Windows users. Check this tutorial to see how to get Let’s Encrypt certificates while running Windows. But I am not recommend you to use Windows for this process, I have tried but failed…

Since we are running on GitLab’s servers instead, we have to do a bit of manual work:

$ ./letsencrypt-auto certonly -a manual -d YOURDOMAIN.com

#

# If you want to support another domain, www.YOURDOMAIN.com, for example, you

# can add it to the domain list after -d like:

# ./letsencrypt-auto certonly -a manual -d YOURDOMAIN.com -d www.YOURDOMAIN.com

#

I only configured the www subdomain for my site. After you accept that your IP will be publicly logged, a message like the following will appear:

Make sure your web server displays the following content at

http://YOURDOMAIN.org/.well-known/acme-challenge/5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM

before continuing:

5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.ewlbSYgvIxVOqiP1lD2zeDKWBGEZMRfO_4kJyLRP_4U

#

# output omitted

#

Press ENTER to continue

Now it is waiting for the server to be correctly configured so it can go on. Leave this terminal window open for now.

So, the goal is to the make our already-published static website return said token when said URL is requested. That’s easy: create a custom page! Just create a file in your blog folder that looks like this:

---

layout: null

permalink: /.well-known/acme-challenge/5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.html

---

5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.ewlbSYgvIxVOqiP1lD2zeDKWBGEZMRfO_4kJyLRP_4U

This tells Jekyll to create a static page, which you can see at cool-blog/_site/.well-known/acme-challenge/5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.html, with no extra HTML, just the token in plain text. As we are using the permalink attribute in the front matter, you can name this file anyway you want and put it anywhere, too. Note that the behaviour of the permalink attribute has changed from Jekyll 2 to Jekyll 3, so make sure you have Jekyll 3.x installed. If you’re not using version 3 of Jekyll or if you’re using a different tool, just create the same file in the exact path, like cool-blog/.well-known/acme-challenge/5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.html or an equivalent path in your static site generator of choice. Here we’ll call it letsencrypt-setup.html and place it in the root folder of the blog. In order to check that everything is working as expected, start a local server with jekyll serve in a separate terminal window and try to access the URL:

$ curl http://localhost:4000/.well-known/acme-challenge/5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM

# response:

5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.ewlbSYgvIxVOqiP1lD2zeDKWBGEZMRfO_4kJyLRP_4U

Note that I just replaced the http://YOURDOMAIN.com (from the letsencrypt-auto instructions) with http://localhost:4000. Everything is working fine, so we just need to upload the new file to GitLab:

$ git add letsencrypt-setup.html

$ git commit -m "add letsencypt-setup.html file"

$ git push

Just because the permalink attribute, I cannot get the correct response from the url above, and get a 404 response. The right response can only curl from the url with .html ending.

For fixing this problem, you can add the following lines in your .gitlab-ci.yml file after Jekyll build the site in the public/ folder:

- cd public

- mkdir -p /.well-known/acme-challenge

- cd .well-known

- cd acme-challenge

- printf "%s" 5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM.ewlbSYgvIxVOqiP1lD2zeDKWBGEZMRfO_4kJyLRP_4U > 5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM

Once the build finishes, test again if everything is working well:

# Note that we're using the actual domain, not localhost anymore

$ curl http://YOURDOMAIN.com/.well-known/acme-challenge/5TBu788fW0tQ5EOwZMdu1Gv3e9C33gxjV58hVtWTbDM

Now that everything is working as expected, go back to the terminal window that’s waiting for you and hit ENTER. This instructs the Let’s Encrypt’s servers to go to the URL we just created. If they get the response they were waiting for, we’ve proven that we actually own the domain and now they’ll send you the TLS certificates. After a while it responds:

IMPORTANT NOTES:

- Congratulations! Your certificate and chain have been saved at

/etc/letsencrypt/live/YOURDOMAIN.org/fullchain.pem. Your cert will

expire on 2016-07-04. To obtain a new version of the certificate in

the future, simply run Let's Encrypt again.

- If you like Let's Encrypt, please consider supporting our work by:

Donating to ISRG / Let's Encrypt: https://letsencrypt.org/donate

Donating to EFF: https://eff.org/donate-le

Success! We have correctly acquired a free TLS certificate for our domain!

Note, however, that like any other TLS certificate, it has an expiration date, and in the case of certificates issued by Let’s Encrypt, the certificate will remain valid for 90 days. When you finish setting up, just put in your calendar to remember to renew the certificate in time, otherwise it will become invalid, and the browser will reject it.

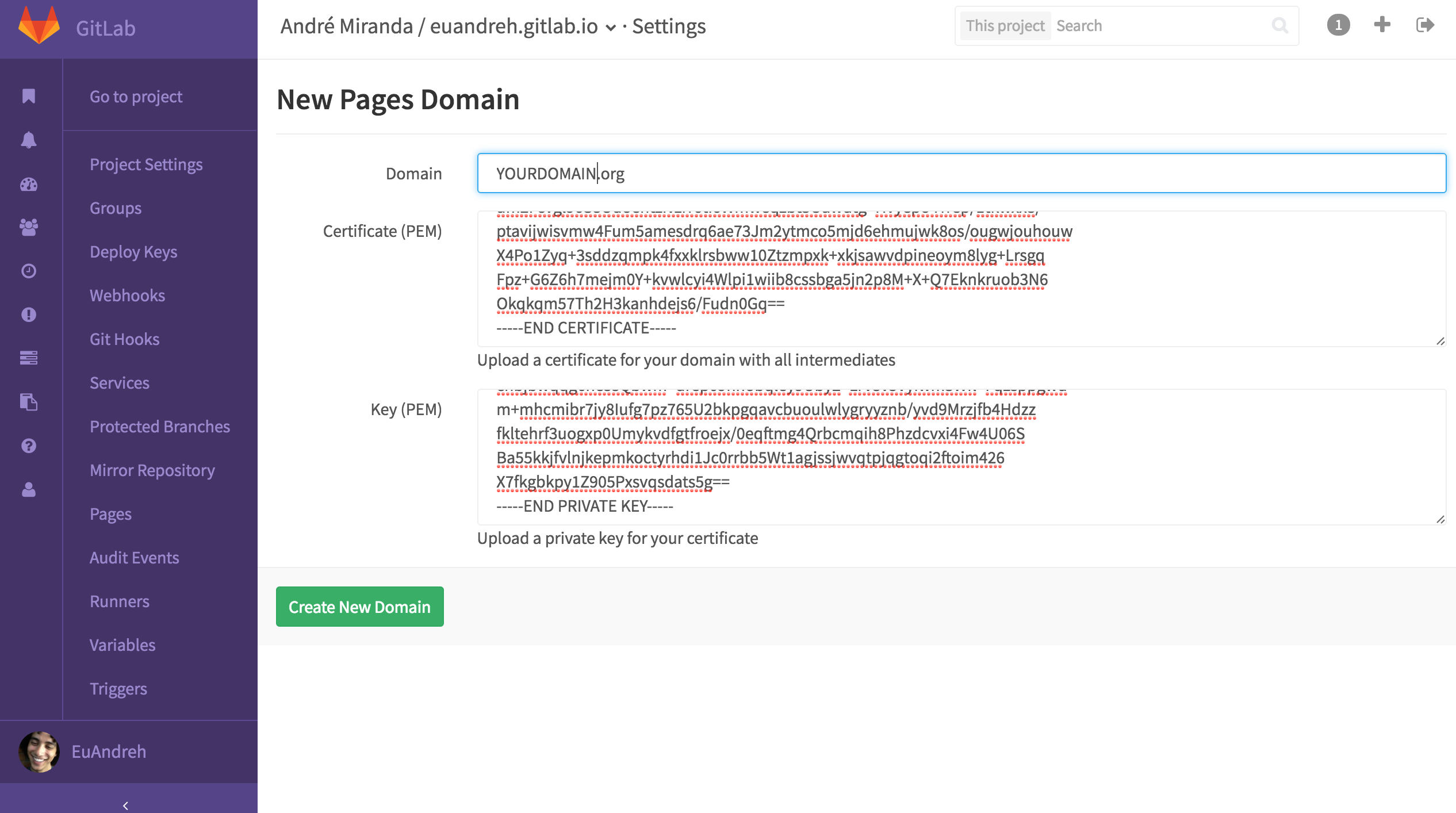

Now we just need to upload the certificate and the key to GitLab. Go to Settings -> Pages inside your project, remove the old CNAME and add a new one with the same domain, but now you’ll also upload the TLS certificate. Paste the contents of /etc/letsencrypt/live/YOURDOMAIN.com/fullchain.pem (you’ll need sudo to read the file) to the “Certificate (PEM)” field and /etc/letsencrypt/live/YOURDOMAIN.com/privkey.pem (also needs sudo) to the “Key (PEM)” field.

You can access your .pem files by using sudo su in Ubuntu with Gedit.

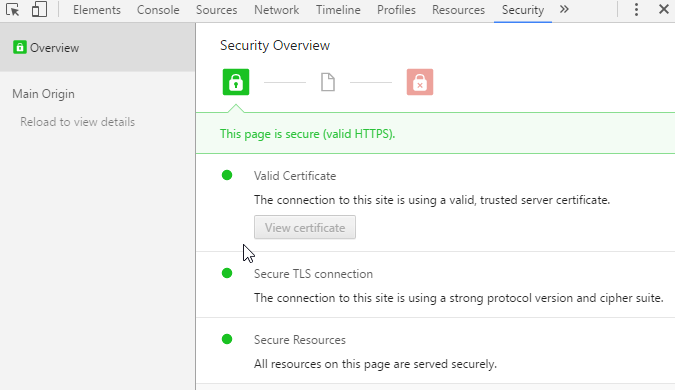

And you’re done! You now have a fully working HTTPS website:

$ curl -vX HEAD https://YOURDOMAIN.com/

#

# starting connection

#

* TLS 1.2 connection using TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA

* Server certificate: YOURDOMAIN.com

* Server certificate: Lets Encrypt Authority X3

* Server certificate: DST Root CA X3

Redirecting

Everything is working fine, but now we have an extra concern: we have two working versions of our website, both HTTP and HTTPS. We need a way to redirect all of our traffic to the HTTPS version, and tell search engines to do the same.

Search Engines

Instructing the search engines is really easy: just tell them that the HTTPS version is the “canonical” version, and they send all the users to it. And how do you do that? By adding a link tag to the header of the HTML:

<link rel="canonical" href="https://YOURDOMAIN.com/specific/page" />

Adding this to every header on a blog tells the search engine that the correct version is the HTTPS one, and they’ll comply.

Internal links

Remember to use HTTPS for your CSS or JavaScript file URLs, because when the browser accesses a secure website that relies on an insecure resource, it may block that resource.

It is considered a good practice to use the protocol-agnostic path:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="//YOURDOMAIN.com/styles.css" />

<script src="//YOURDOMAIN.com/script.js"></script>

JavaScript-based redirect

There is, however, a case where the user specifically types in the URL without using HTTPS, and they’ll access the HTTP version of your website.

The correct way of handling that would be to respond with a 301 “Moved permanently” HTTP code, and the browser would remember it for the next request. However, that’s not a possibility we have here, since we’re running on GitLab’s servers.

A small hack you can do is to redirect your users with a bit of JavaScript code:

var host = "YOURDOMAIN.com";

if ((host == window.location.host) && (window.location.protocol != 'https:')) {

window.location = window.location.toString().replace(/^http:/, "https:");

}

This redirects the user to the HTTPS version, but there are a few problems with it:

- a user could have JavaScript disabled, and would not be affected by that;

- an attacker could simply remove that code and behave as a Man in the Middle;

- the browser won’t remember the redirect instruction, so every time the user types that same URL, the website will have to redirect him/her again.

Wrap up

That’s how easy it is to have a free HTTPS-enabled website. With these tools, I see no reason not to do it.

If you want to check the status of your HTTPS enabled website, SSL Labs offers a free online service that “performs a deep analysis of the configuration of any SSL web server on the public Internet”.

I hope it helps you :)

Related posts in Jekyll

Related posts in Jekyll  Better quality of Goog...

Better quality of Goog...  Host Jekyll Site on Go...

Host Jekyll Site on Go...